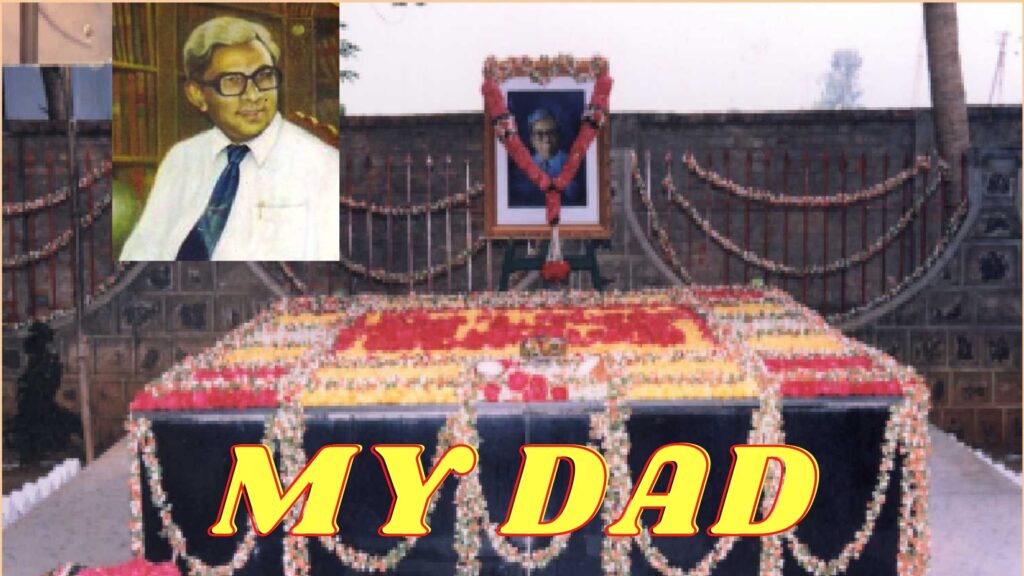

(This is a brief sketch of my dad, although departed thirty years ago, how he represented as my life model. Reading, teaching and discipline are the values he had inspired that even today I have not stopped listening and imitating him.)

My dad died at the early age of 56 – a massive heart attack claimed him, a bitter tragedy and so shocking, I barely could understand how it unfolded on that dark night; the whole ordeal was a nightmarish cry for help. All fell in a matter of minutes; I found staring at blankness and a dead-end situation – a life without the protective presence of my dad.

It was early Nineties and a February evening. I just returned home, climbed three flights of stairs, at once noticed something unusual; I saw my dad arc forward, gripped the railing in the corridor as if taking support not to fall in a heap. His eyes hid in the dark. Had there been a share of light around, I might have noticed the last glint of a plea in his eyes before he collapsed dead in my arms. Next few seconds, in confusion and panic, I had to gasp hard to bear his hefty body down and check the vitals. I knew he wasn’t lucky to make it to the hospital.

A devastating scenario played before me. It’s about the anguished plight of my mother; she lay under the surgeon’s scalpel a day before, how I should wheel her out of the hospital, and the uneasy question, who would inform about her husband’s death. She has to console herself; witness and supervise the last rites of her life partner.

My dad’s story weaves around many failures and few rewards. For over fifteen years in carving his identity and his enterprise to stay afloat; I never saw him at home, but taking to task the many hiccups that choked the fledgling school. Barely had I seen him engaged in family time, so in no way I felt a likely heir to the educational institute – the family enterprise, over the years, which grew vast and complicated to manage. I was then twenty-nine, married, and had to care for two younger brothers.

My dad’s influence upon me runs deep. It felt something like a squeeze of breeze, diffused onto me as if I’m inhaling all his intellectual odors; it’s all about books, reading, manners of self-restraint, and self-discipline.

Throughout my growing years when I saw him I feared his inscrutable ways; his moodiness discouraged any favor of intimacy. He was never a cheery type like those you can laugh around loudly, make you sit on a bicycle, and amuse you around. I remember how it scared me not knowing what prompted his frequent short-fused temper – those loud reprimands at any hour of the day, his sharp eyes spilling anger and restraint, the only time he touched me when bashed for anything I did that displeased him. I recollect how I grew up bottling the hurt. When I look back, I felt ashamed of being the eldest; I became handy to his fits of anger that never stopped even after getting married.

Slowly, and mellowed after I got married, my perception of how I received my dad had changed altogether. When I discovered a refined cloak of his nature, I built a new picture of him, something pragmatic revealed to me, which I never came upon before. He carried within him a transformative, redeeming essence – like a hard nut hiding flavored nectar, that outshined whatever his short-tempered pattern that always seen me oscillating between dread and hatred in his proximity. It’s all about his love for books, the way he huddled on a cot, early morning, a thick blanket wrapped around, and a text in his lap, lost to the world in reading.

This image played in my mind again and again, like comic strips watched by kids. It evoked a rap of yearning – a mix of hurt and sentiment that permeated solemnity like a powerful engraving in a museum. Though I lost him thirty years ago, I cling to his heuristic memories fluttering like a classical song and tune.

I picked up that habit – the love for books, a passion for reading. I think it’s the best, life-enriching, lifesaving gift any father would lavish upon his children, like a rhythmic heartbeat, like a melodious song, that storm of passion for books docked inside me since then.

The image – my dad poring over a book, like a divine creator, I believed, waited by my side like a glowing halo showing me the path I must navigate through the wilds and woods of my life. I guess the habit of self-learning never let me down; instead reminded, I always keep telling myself, that, “I have to keep learning, keep evolving, and maturing.”

In 1955, India then tagged a third-world nation, seemed like a black and white era movie. They rationed food and necessities, getting anything available only after laboring in long queues. And fewer trains, no telephone, and less money. Such was the disheartening prospects that prevailed when my dad achieved a doctorate in Physics from the famous Banaras Hindu University, followed by a brief stint in Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, and later a four-year sojourn in the USA at the University of North Carolina. His post-doctoral pursuit in the US cut short abruptly because of the untimely death of his elder brother. He returned to his native place, Vijayawada, Andhra Pradesh, in 1964.

Framed in medium height, he held a confident stride with a triangular face crowned with thick black and gray hair. His eyes were small and piercing with years devoted to study, which appeared at once ready to absorb anything from his library, where I often found him early in the mornings and late nights.

In the early seventies, job prospects in our small town were flimsy. A few colleges hesitated to hire my dad not because he didn’t suit teaching aptitude; his doctoral thesis and high academic endorsements intimidated the most, who sat to interview him for an assignment.

Some years later, I turned twelve when I saw him huddled with some of our relatives, mooted a proposal to start a primary school – the decision which later was to become a watershed movement in his life: financially, professionally, and socially. For my young eyes, it amazed me at the sudden prospering tide where the family’s prospects rose to eminence. A school par excellence, Kennedy High School was born.

In its early days, the school my dad planned looked more like a cattle shed, with a low-hung thatched roof. One has to bend forward to step into the ‘classrooms.’ With no proper flooring, it’s a vast space with roofing made with straw, bamboo, and dried Palmyra leaves. The children walked in in designated uniforms; five decades back, it’s seen as a novel idea. They squatted on the floor separated by crude bamboo mats, notes in their laps, and teachers’ shouting their lungs out where all voices merged into a loud mass of decibels. The scene looked like a crowd of children ran amok into a sweet shop screaming naively all in one go.

For me, it’s an unforgettable profile – his head buried in a thick theoretical book, sat on a wooden chair and a small bench before him. It’s amusing the traits accrued spending years in research labs never left him, even while coaching a class of kids; I found him wearing a white knee-length coat – as if he saw himself pouring over complex mathematical calculations in a lab. Instead, oddly and actually, he faced a chatter full of younglings. His powerful sense of self-worth was what I realized made him do what he had done for over a decade and a half until premature death blew him out: teaching the young kids. It captivated me as a profound lesson of humility. I strived to walk in his footsteps – a mantra for a peaceful life; I was to go like him and his commitment: to be a teacher.

He loved to stay close to his extended family: his two older brothers and their sprouting offsprings. We were all bunched together in our ancestral home, compact space of five rooms roughly measuring to accommodate, at present scale, a double size bed and a maneuvering space of about two feet. We are then four to squeeze in, but it embarrassed me to imagine how my two uncles occupying the other rooms comforted themselves in the tiny spaces with five and eight kids each. And a small room in one corner saw our grandparents in their seventies huddled themselves and who led a fiercely independent lifestyle. The rustic household was complete with a kitchen shared by each aunt occupying a segmented corner with a kerosene stove. Lunch and dining meant a noisy get-together – a smiling and gossiping affair. I’m still nostalgic about the strong strings of security and esteem I had collected in the school-boy days in my grandparent’s presence; their fragile hands swung the cradle of my moral conscience and the docile personality.

These were a stock of few faint memories I can illuminate. They stayed on my mind’s palette as active as something like a colony of ants twirling in a frenzy, and sometimes I get an urge to go back to those days and muse for a while when I spool back to recapitulate my yesteryear’s splendor.

One feature – how my dad perfectly dressed and went out to work was itself an identity statement in the early seventies, which drew many eyes on him. He thus attained smiles of admiration as he pedaled on a bicycle, with an ironed white terry cotton shirt neatly tucked in pleated black trousers, along the street. The elegance turned full circle with a tie and a brooch which I remember rested over the curve of his conspicuous belly. I choose to etch this iconic image in my memory. Years later, I too assumed an expression of style, followed the silent model he had set just by being what he was all the time: unassuming and never self-conscious.

Now, I’m 56 (the unedited version first posted in 2017), precisely starring at the same milestone wherein my dad succumbed to cardiac arrest.

I’m blessed to have such a silent role model as my dad, but his untimely demise threw me into a dark tunnel of a void – wherein I confronted the eventful issues that had come up no sooner than four days after we buried him. I still wonder, when I sit and watch at the three decades of the rushes, the immediate pressures I had shouldered: the family, my ailing mother, a school buzzing with three thousand students, its administration, financial urgencies – I felt like a novice thrown into a high sea: dangerous and survival unlikely. But isn’t that I have had handled the transition ably and stayed true to my dad’s wisdom, steered with calm thoughts, protected my family and the school? I ask myself.

His memories, his way of life, though brief but profound enough, bonded well as if nothing else mattered, rang in my ears as if I were hearing the beat of my dad’s heart – as though sending trills of care and caution. They showed up as flashes of light on my path strewn with struggles, helped maintain a manner of gainful attitude, been supple, and never shied away from hard lessons that came my way. Even after three decades of his absence, I never stopped learning, growing; I never fail to see his magic aura, “knowing how to rescue the inner self, is the key to true peaceful living.”

Today, I wear his memories as armor, sound, safe, and conservative like a watchful mother peering from a distance, her child walking down; head up, to meet the challenges.