When I stepped out of my hotel room on a blazing weekend morning, it was not even six, met with a burst of windy heat swept upon my face. The previous night, I got a hint of the sultry summer’s punch when I roamed about a few paces in search of a dinner spot. The sweat itched my hair and flowed down my legs. I couldn’t help wondering how the spawning hot spell would roast me when I was to visit the local fish market for a shoot the next day.

I was on a two-day visit to Kakinada, a growing business coastal city of Andhra Pradesh. I nourish a nostalgic connection to this one of India’s most well-planned cities. I was born in this place six decades ago: a well-known hub of temples, good food, and a string of theatres temptingly lined in one street.

Since then, I have seen the evolution of this small, passive town to a chaotic, noisy, flourishing business city. But I hold the decades of memories in good detail – of my formative days, of those innocent reels of sentimental versions that never seemed to fade away. Whenever I call on twice or thrice a year, I delight as if stepping into my ancestral home, which had gone unrecognizably changed over decades. I somehow wouldn’t let go of the troves of those enduring impressions. As a child, I listened and grew up walking through the old charm and beauty of this shy, timid persona of an unseen town, something sensible and as obedient as a young bride sitting on a marriage altar.

Following a suggestion of one of my friends, on the early Sunday morning before the summer sun could decide to position itself harshly or mildly, I drove off, the camera gear rocking close by my side, to a local fish market to test my street photography initiative. By nature, I saw myself as a self-conscious type that, in public places, I felt unguarded, faltering, and as if all eyes were questioning, “Hey guy, what you are up to with that flashy camera?” I would never jump that fast, that casually when I find myself among street-smart groups. Indeed, I’m aware, and it’s not a suitable makeup recommended if you want to mingle in the streets taking pictures.

I passed through the Sunday market crowds on the city’s main roads to reach Matlapalem village, thirty kilometers away and towards the Bay of Bengal coast.

The early morning fog seemed so thick that it felt like driving through a cloudy white cave, the black roads leading me to a magical destination. The roadways to where I had to go appeared clean, and sparsely any traffic seemed present. Throughout the thirty-minute ride, everything seemed to pass in ghostly shadows in the fog. Then it opened before me, the most curious marketplace I have ever seen. When I peered through my camera, the scene had all the factors to scare my wits.

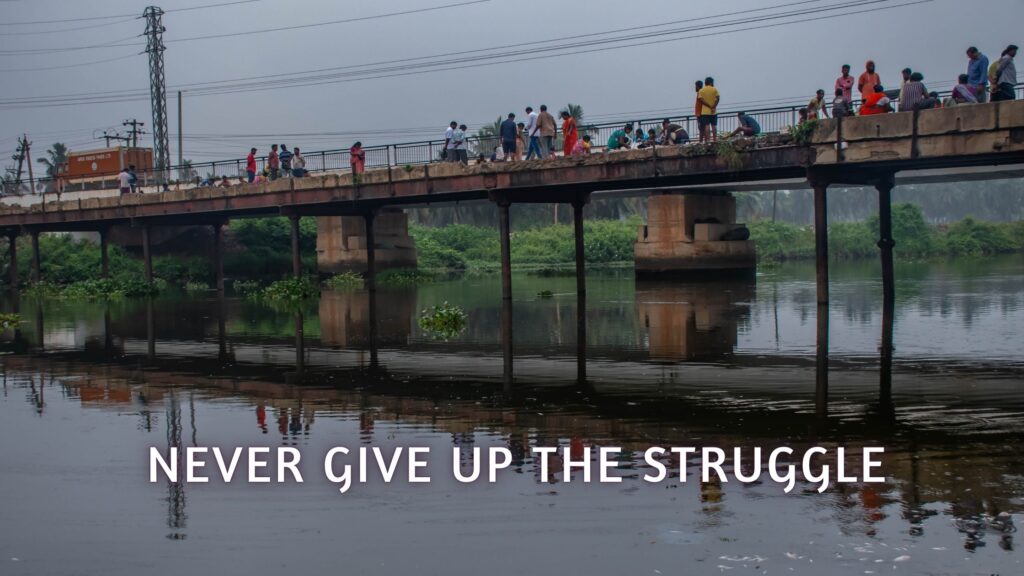

The fishing and selling crowds are milling about on an unprotected, crumbling, far-outlived concrete footbridge.

I pulled my car off the road and parked not to obstruct any regular traffic. It took some startling time to take in the strong-smelling fish market scene that’s abuzz with cutting, chopping, and scraping the largest varieties of fish heaped in scores of mounds. And all done clumsily by women in gaudy colored saris, using the old-style cutting knife mounted on a small rectangular wooden plank that can sit on any surface. Held by the women’s calloused hands, the bulk of the fish conveniently sliced itself against the vertical sharp curved blade.

Amidst the hard job, the women’s faces shown with a resigned poise carried out evidently on a junked bridge perched on wasted pillars jutting out from the canal below. It presented an “I can’t believe what I’m seeing” image – a scrapped-off passageway that wore an insecure look, giving me a reaction that it’s not been maintained duly for ages. Added to the veiled danger, a deep gushing canal flowed below, waiting for calamity. The slippery narrow bridge is hardly six feet wide and has no protecting railings. It’s like an extended naked cemented slab laid across a stream. With one wrong slip, the green waters below gobble you up in a minute.

Tens of women immersed in their chopping skills, with no safeguards, squatted on either side of the hazardous bridge; seen from a distance, we get an illusion that it’s hanging in mid-air. Something similar to the scenes we see in some adventurous jungle movies. Despite this, they seemed relaxed, friendly, and talkative, even adjusting their saris when I asked for permission to click a snap. The casual acceptance of my presence, slinging a camera, I wondered, perhaps, because of the widespread familiarity of many social and visual platforms. After a while, I felt settled to request as much liberty and as many various angles to choose to frame them. The ladies’ sociability – carried some hidden concern to the task at hand, and the customers pestering made me ignore, for the whole three hours, the risky environs I was sneaking about and within which their daily trade flourished.

Now I seemed to be in a fix as I held my camera, unsure how cautiously I could manoeuvre without faltering on the wet surface matted with ripped-off fish scales, how I would tread along the length of this unprotected platform where I was to seek my subjects, here the genial fisher women busily immersed in sizing up their pink, shiny fish with their stilled eyes. I turned and twisted like an acrobat to manage a sharp focus and secure a good visual output. Walking about, it looked like a cringey situation I had never stumbled upon. I noticed my shoe stamping on filthy severed heads of discarded heaps of fish and clots of wet blood leaking out from their tiny mouths. For a low-angle focus, if I tried to bend or attempt to squat, I could sense a soft touching mass – a small mound of rejected lots of dead prawns. I noticed many such oodles of slimy leftovers all over the moist surface. Perhaps, a little later, I imagined, the lots might go down and get washed along the canal.

After three hours in an irritating sizzling sun, my eyes got washed down in sweat, but the women, as sharp and rigid as knives, seemed to work with no break. I could see the people walking up and down in small crowds, at their loudest found bargaining and collecting their cleaned and properly sliced marine wares. I have learned that the market comes alive every day at three in the morning, and before eight, most pack themselves back home. The same incredible routine begins the next day. These strong women back home are the champions of raising a healthy family. I wish everyone would recognise the women I’m presenting in the pictures: their dominance, resilience, fearlessness, and grace.